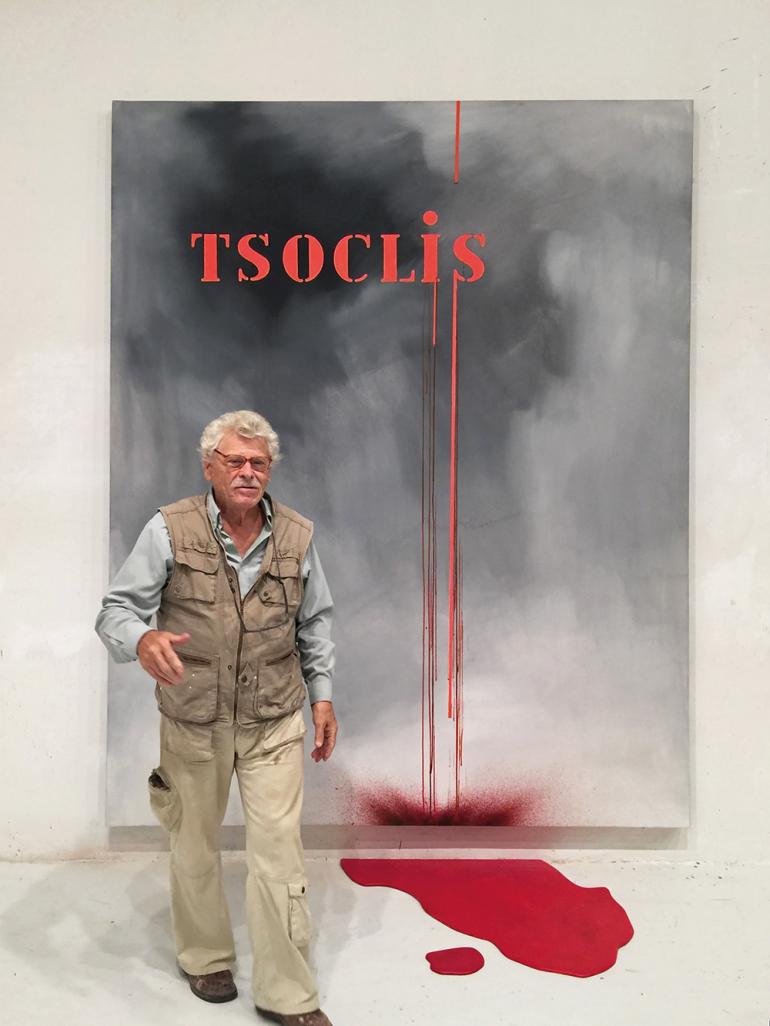

Costas Tsoclis : The Artist

Through his works, this globally acclaimed artist communicates on a universal level.

Born in Athens to a poor family in 1930, Costas Tsoclis was the sixth of seven children. Having completed only elementary school, he began working tirelessly as an assistant in cinema decor. During breaks, he would recite Cavafy. He entered the School of Fine Arts as an exceptional talent, secured a scholarship in Rome, then moved to Paris and later to Berlin briefly. His name gained international acclaim as he engaged with the most prominent art dealers of the time and exhibited his works in major museums. In 1984, after almost 30 years of absence, he returned to Greece –always Greek– now international. In 1986, at the Venice Biennale, he introduced “Living Painting” which birthed a global artistic movement. Costas Tsoclis was born not just to make a mark in the field of visual arts but to breathe new life into them, dispelling the dust of the routine, the expected and the conventional. Today, at 93 years old, he likes to be called “unpredictable and unconventional” in his work and life.

Let’s go back to the young Costas Tsoclis. What was the pursuit in your life back then?

There was no pursuit. I lived and that was enough. I played, fought, took risks, worked and learned like every child does under the conditions they find themselves living – either hell or paradise.

When did you realise that art was your destiny? How did you become an artist and not something else?

Because I believe it’s inappropriate to turn our lives into mere reading material to fill the traveller’s idle time, let’s suggest something more meaningful. Let’s talk about art, which is everywhere, even if we are not conscious of it. We all engage in artistic expression throughout the day: from the moment you decide on the day’s attire, choose your shoes, decide on the amount of makeup, or whether to shave or grow a beard, you inherently become a visual artist. While you quietly sing in your bathroom, you are a musician. When you write a letter, you are an author, if not a poet. When you dance, you become a dancer. Even if you don’t possess talent, it’s there.

What role did talent play in your journey?

Some individuals excel in specific domains of human activity (what we call talent). Consequently, others admire and emulate them, placing trust in their abilities. Talented individuals, recognising this, assume responsibility and take themselves seriously. This realisation propels them to strive for excellence, engaging in experimentation and accumulating valuable experience. They entrust their sense of vocation with the responsibility for their social participation. I, too, align with this pattern and am no exception to this rule.

What is the difference between a good artist and a great artist?

The eminent artist imparts knowledge; often, he creates from the realm of non-existence. In other words, when the lexicon of his art lacks the requisite words for self-expression, he innovates and discovers new ones. A proficient artist learns from the master, relying on their ideas, and occasionally, with these novel expressions, outshines the originator – to the credit of the latter, of course. Conversely, there exist less significant artists, those who abuse the ideas of the great, accelerating audience fatigue and necessitating change. Even these artists serve a purpose, and we should not disdain their contributions.

What were the highlights of your artistic career?

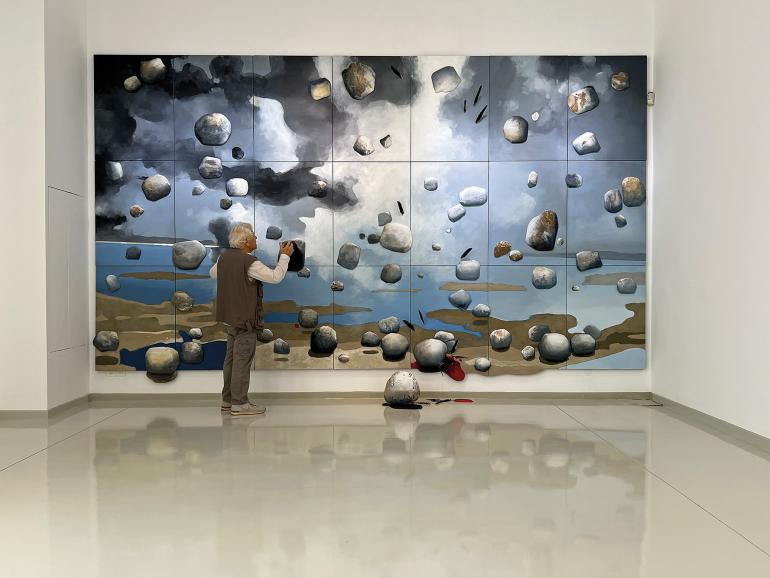

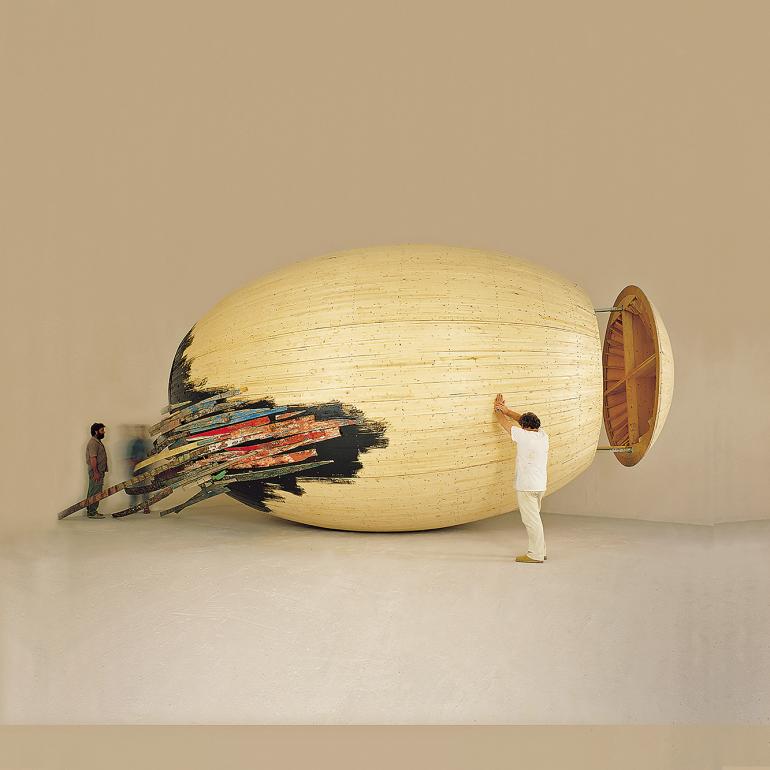

Nothing is guaranteed. As the saying goes, “Time will tell.” When you take action, you’re always aiming for a masterpiece. That’s why the life of an artist, no matter how successful, is laden with small or significant setbacks and moments of bitterness. Yet, sometimes, unexpectedly, you triumph. Then, you pause, waiting for others to recognise it. And this waiting is agonising. Indeed! I experienced some joyful moments during my career. I’m specifically talking about the period from 1967 to 1972, focusing on the series “Objects-Situations” – crates, doors, windows, stairs, pipes, wells, chairs and tables comprised my repertoire of work at that time. Not all of them were painted. Some were objects crafted by my hand, imbued with a sense of space and solitude. I was living in Paris at the time and these works saw success in Europe. Subsequent endeavours, perhaps deemed less significant, and further struggles ensued, yielding commendable works and additional moments of joy until 1985. During that year, with the presentation of “Harpooned Fish” and the moving “Portraits” at the 42nd Venice Biennale, I introduced a novel art form – “Living Painting.” This artistic expression, pursued by thousands of artists worldwide, albeit with distinct approaches and motives, likely without awareness of its origin, was a significant development. Since then, I’ve crafted numerous pieces in this fusion of classical painting with modern technology. However, a consistent theme in my body of work has been the humility of the subjects that have inspired me throughout the years. Initially, it was the objects I previously mentioned, and later, even more unconventional ones found scattered on the streets: a discarded tin can, crumpled newspapers, a Coca-Cola lid, a piece of wood, a string, a wire with a nail, a half-burnt match, a stone, some dirt and a brushstroke – all integrated into a painting where they served as both subject and material.

And on a larger scale?

I’ve undertaken three notable interventions in public spaces. Firstly, in 1984, I converted an abandoned, neglected Athenian neighbourhood in Plaka into an artistic masterpiece using mirrors. Then, in 2006, I transformed the ruins of a village (Monastiria in Tinos, specifically) into a landmark, offering it a brief second life. Finally, in 2012, I turned Spinalonga, the islet of lepers, into a museum and tribute to the countless individuals who, as anonymous figures, sacrificed their flesh and lives in this inhospitable place. The project was titled “Tsoclis, You the Last Leper.” Currently, I’m engrossed in creating a monumental piece measuring 14.5 metres in height by 17 metres in width, which we plan to showcase in October 2024 at the Public Tobacco Factory on Lenorman Street. Through this artwork, I aim to convey the profound awe that has gripped me in recent years, brought about by revelations and advancements in science. This sense of awe has prompted me to reflect on how various elements –be they thoughts, machines, electronic devices, medicines or even food– that I and others utilise are often employed without a comprehensive understanding of their origins, functions and sources. Hence, I strive to articulate this sentiment of mine, this sense of unknowing, through novel abstract forms and primary colours and elements that are perplexing yet undeniably genuine. It represents an alternative reality that presently governs our lives unbeknownst to us. However, my most significant endeavour is unquestionably the Museum in Tinos – an enduring cultural legacy for the island, our country, the realm of art and my body of work. This accomplishment owes much to the unwavering commitment of Chrysanthi Koutsouraki, who has stewarded the museum since its inception and, I hope, will continue to do so for many years to come. She has also curated the Catalogue Raisonné of my work, effectively encapsulating the narrative of my life.

Who is Tsoclis in one word?

An artist.

_______________________________________

INTERVIEW : ROMINA XYDA

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

The Legacy of Ernst Ziller

Mitos : The Thread of Greece

The Northern Miracle